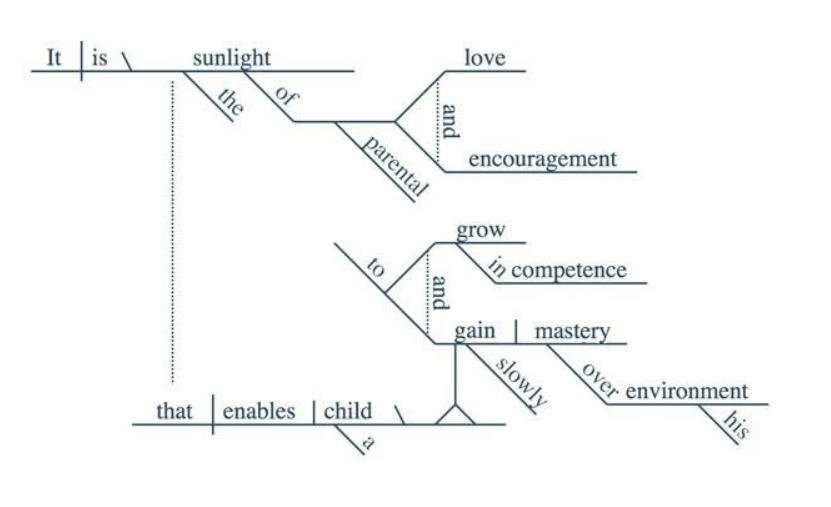

Today is the second class in your current four class set. We will start class with a casual conversation. Our material today is about net neutrality. Please listen and follow the transcript. We will finish class with a sentence diagram.

SYLVIE DOUGLIS, BYLINE: NPR.

(SOUNDBITE OF DROP ELECTRIC SONG, "WAKING UP TO THE FIRE")

DARIAN WOODS, HOST:

This is THE INDICATOR FROM PLANET MONEY. I'm Darian Woods.

WAILIN WONG, HOST:

And I'm Wailin Wong. For the last couple decades, there is this tech policy issue that keeps resurfacing. People were out there rallying in 2014...

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED CROWD #1: (Chanting) Keep the internet free. FCC.

WONG: ...And again in 2017.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: When I say internet, you say freedom. (Chanting) Internet.

UNIDENTIFIED CROWD #2: (Chanting) Freedom.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: (Chanting) Internet.

WOODS: Sweet, sweet internet freedom. And what these demonstrators are rallying around is the principle of net neutrality. This is the idea that content on the internet should be treated equally and that internet users get to decide what they do on the web, not internet service providers.

WONG: What net neutrality supporters don't want is for a broadband company to tell their customers, for example, you can send an email but not stream a TV show - or, hey, you'll get higher speeds for a particular streaming service.

WOODS: The Federal Communications Commission first enacted net neutrality rules in 2015 under President Obama. Then the Trump-era FCC repealed those rules.

WONG: And when that happened, net neutrality advocates warned of a dark future, the end of the internet as we knew it.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

WOODS: A scary prospect indeed. And so we wanted to figure out whether that doomsday scenario came to pass. It's an important question, as the current FCC, with a new Democratic majority, moves ahead with plans to restore net neutrality rules.

WONG: And yet most of us probably haven't noticed much of a difference. It's like, it's the end of the internet, and I feel fine.

WOODS: Yes, but the reality isn't that simple. So today on the show, we check in on this perennial debate to see how the internet has fared without net neutrality.

WONG: One of my earliest internet memories is getting those AOL CDs in the mail that came with maybe a few hours of free usage time on it. This was back in the '90s. How about you, Darian? What's your earliest internet memory?

WOODS: Yeah, a lot of negotiation with my parents about using the phone, which, if you remember dial-up modems, couldn't be used at the same time as the internet.

WONG: Oh, yes. I could make that sound right now if I wanted to.

WOODS: Yeah. Yeah.

WONG: So both of us have some memories of the '90s internet. Barbara van Schewick is a professor at Stanford Law School, and she says in the early '90s, the idea of an open internet was the default. The internet service providers, even if they wanted to, could not really interfere with what people were doing online.

BARBARA VAN SCHEWICK: Data travels over the internet in packets, and when the internet first evolved, the internet service providers weren't able to look into these data packets.

WONG: But in the mid-'90s, the companies gained the technical capability to inspect these data packets.

VAN SCHEWICK: It allows the internet service providers to see, oh, Barbara is going to the website of The Wall Street Journal, or, you know, she is chatting with her friends. And so that then triggered this debate about should we through - now through rules ensure that internet service providers can't block websites or otherwise interfere with what we are doing online?

WOODS: There was debate but no enforceable rules around net neutrality until 2015. That's when the Federal Communications Commission adopted a new set of rules called the Open Internet Order.

WONG: This order gave the agency the legal authority to enforce bans on certain practices, like blocking content or favoring some kinds of content over others.

WOODS: And these rules just lasted for two years. In 2017, the Trump-era FCC repealed them. The FCC chairman at the time said a lighter touch on regulation would encourage more investment and competition in the broadband industry.

WONG: But advocates for net neutrality sounded the alarm. They warned that broadband providers could start charging people more to use certain applications, or some customers could access internet fast lanes while everyone else would be stuck with slower speeds.

WOODS: Barbara is a proponent of net neutrality, and in her view, what ended up happening after the 2017 repeal was subtle, maybe so subtle that most people didn't even catch on.

VAN SCHEWICK: Internet service providers have started to slowly exploit this lack of oversight and limit what people can do online. And so it's like the boiling frog where the water gets hotter and hotter, and the frog doesn't notice because change is so gradual.

WONG: Barbara points to two practices that she says crept in during the last few years. No. 1 is zero rating. This is when an internet service provider says certain kinds of content don't count towards a customer's data cap.

WOODS: For example, in 2016, AT&T introduced a program called Data Free TV. AT&T customers who were also DIRECTV customers could stream DIRECTV without that counting toward their monthly data usage. Now, AT&T owns DIRECTV.

WONG: So Barbara says the problem with this kind of program is that service providers can give certain applications - like, say, the ones they own - a competitive advantage.

VAN SCHEWICK: Hey, if you watch our video services, then we won't count them towards your data cap. But if you want to watch YouTube or Netflix or, you know, the Sunday services at your local church, they will burn through your data.

WOODS: AT&T suspended Data Free TV along with similar zero-rating programs in 2021. This was in response to a net neutrality law that the state of California enacted that year. AT&T said because the internet doesn't recognize state borders, it had to effectively apply the California law in other places, too. AT&T also said it's committed to the principles of an open internet.

WONG: So that is zero rating. It's one practice that Barbara thinks has quietly turned up the heat on the boiling frog. The second practice she points to is called throttling. This is when an internet service provider intentionally slows down someone's speed.

WOODS: And in 2019, researchers at two universities published an analysis of a year's worth of web traffic. And they said that between 2018 and 2019, wireless carriers in the U.S. routinely slowed down services like Netflix and YouTube. According to their report, this happened even when networks weren't overloaded.

WONG: Kevin Werbach is a professor of legal studies and business ethics at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. He also worked at the FCC in the '90s, and he says he's heard about incidents of throttling and zero rating. But overall, the fears of the net neutrality repeal ushering an internet doomsday were overblown.

KEVIN WERBACH: There are those on the pro-net neutrality camp who said that if net neutrality goes away, we won't have an internet or, you know, broadband companies will tremendously clamp down, and you won't have any applications on the internet that aren't paying them. We haven't seen too much of that.

WOODS: Kevin says there was never really a period after the repeal where broadband companies could make drastic changes, and that's partially because of the new net neutrality rules at the state level, not just in California but also in places like Oregon, Maine and Washington.

WONG: And the FCC was sued in federal court for its decision. That process took a couple of years to play out. We should note here that NPR's legal counsel filed comments with the FCC on behalf of the public radio system in support of net neutrality rules.

WOODS: But Kevin did flag a concern about the rollback of the net neutrality rules.

WERBACH: The real problem with the FCC's decision was it was the FCC just stepping away and saying, we're not going to even have oversight. So it's really more about that, about having a cop on the beat.

WONG: So think back to Barbra's metaphor with the boiling frog. People in the tech industry or policy circles can argue ad nauseam about whether the water temperature is changing and how much they think it's increasing. But because the FCC walked away from regulating the broadband companies, there's no government agency actually taking the temperature.

WOODS: Right. So let's say somebody notices their internet speeds have slowed to a crawl. They accuse their internet service provider of throttling, and the broadband company says, no, we're just managing capacity on our network.

WERBACH: That's really the challenge. Why are they throttling? That's something that's typically not going to be obvious to you as a customer. And we no longer have a tool in the toolkit for the agency to investigate and to figure out what to do.

WONG: And Kevin says as the net neutrality debate starts up again, he's less concerned with the details of the rules themselves and more focused on shaping the role of the FCC.

WOODS: Last week, the FCC officially kicked off the process for restoring net neutrality and flexing its regulatory muscle again. The public will get a chance to submit comments.

WONG: Looks like some people might be, you know, dusting off their old protest signs from 2017.

WOODS: Or even 2014 if they're super vintage.

WONG: Ooh. You know, arguing over net neutrality never goes out of style.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

WONG: This episode was produced by Julia Ritchey with engineering by Robert Rodriguez. It was fact-checked by Sierra Juarez and edited by Dave Blanchard. Kate Concannon is our editor, and THE INDICATOR is a production of NPR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)